Every day, Stephen King sits down and writes 2,000 words. More when he was younger. When he finishes a novel he doesn’t take a break. He either moves on to short stories or, if he has some juice left over, he’ll write a novella. Sometimes he’ll let a completed manuscript lie fallow for a while, moving on to another project, then coming back to it later. He may work on a new manuscript in the morning, and rewrite an older one at night. We always think of an author’s biography as being directly related to their work, matching publication dates to events in their lives, but writers live with a book when they’re writing it, not when it’s released. And because King is constantly composing, it’s hard to find any clear correlation between the life and the books because it’s almost impossible to figure out when he actually wrote them. Was he noodling on something for years before he came back to it? How long did a manuscript lie fallow? The best I can do is educated guesswork.

King has published three collections of novellas, and we have to assume that the stories they contain were written after he finished bigger novels. But which ones? I’ve been trying to figure out when King wrote the novellas in Full Dark, No Stars and it’s almost impossible. And it’s driving me crazy, because this collection, like each of the novella collections before, moved King in a new direction.

King’s first collection of four novellas, Different Seasons, was published in 1982 and we know that he wrote “The Body” in 1974, right after he finished ‘Salem’s Lot. He wrote “Apt Pupil” around 1976 after he finished the first draft of The Shining (which took him six weeks!), and “Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption” was written in 1977 right after he finished The Stand. He wrote “The Breathing Method” in 1981 or 1982 because the collection needed a fourth novella to round out the page count. So while we point to Different Seasons and 1982 as being the year King demonstrated he could write so much more than horror with “The Body” and “Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption” they were both written almost a decade before. They simply sat in his drawer for years.

King’s next novella collection was the hazily remembered Four Past Midnight published in 1990, a career low point for King. His publishers wanted him to write more horror, but his newfound sobriety had left him feeling dry and he was worried that he wouldn’t be able to write anymore. Four Past Midnight was hailed as a “return to horror” for King, but it feels hesitant, and the stories sound more like faint whispers than the full-throated, genre-defying, confident roars of Different Seasons. Now, almost 20 years after Four Past Midnight, comes Full Dark, No Stars. When it was published, King was on a roll, returning to his full powers after health problems in the early 2000s and what he described as another dry patch that left him feeling like he’d lost his knack for short stories. But now, he was coming off a string of massive books. Lisey’s Story, one of his personal favorites, Duma Key, his most accomplished novel in years, and Under the Dome which, no matter what you might think of it, was a huge, exhausting undertaking. They were followed immediately by Full Dark, No Stars, its title taken from a phrase he’d been toying with in his novels for years, appearing first in Cell (2006), then in Duma Key (2008).

King’s next novella collection was the hazily remembered Four Past Midnight published in 1990, a career low point for King. His publishers wanted him to write more horror, but his newfound sobriety had left him feeling dry and he was worried that he wouldn’t be able to write anymore. Four Past Midnight was hailed as a “return to horror” for King, but it feels hesitant, and the stories sound more like faint whispers than the full-throated, genre-defying, confident roars of Different Seasons. Now, almost 20 years after Four Past Midnight, comes Full Dark, No Stars. When it was published, King was on a roll, returning to his full powers after health problems in the early 2000s and what he described as another dry patch that left him feeling like he’d lost his knack for short stories. But now, he was coming off a string of massive books. Lisey’s Story, one of his personal favorites, Duma Key, his most accomplished novel in years, and Under the Dome which, no matter what you might think of it, was a huge, exhausting undertaking. They were followed immediately by Full Dark, No Stars, its title taken from a phrase he’d been toying with in his novels for years, appearing first in Cell (2006), then in Duma Key (2008).

1922

King doesn’t write a lot of historical fiction, but when he wrote “1922” he was also in the middle of writing (or rewriting) his massive, yet-to-be-published historical novel, 11/22/63. He’d go on to write more historical fiction in stories like “A Death” in 2015 but this was only his third attempt to write a piece set in a past era he didn’t live through himself, without a contemporary framing story (as in The Green Mile), that attempted to capture the language and writing style of that period. The first attempt? His short story “Jerusalem’s Lot” published in Night Shift all the way back in 1978. The second was “The Death of Jack Hamilton” written in 2001.

Inspired by Wisconsin Death Trip, set in Hemingford Home, Nebraska (which had featured in his fiction before), it’s a grim murder ballad sung in stark language. A farmer who believes that his wife wants to sell his land out from under him enlists his son in a murder scheme, but the guilt over what they’ve done festers and grows until his teenage son loses his mind, gets his girlfriend pregnant, busts her out of a home for unwed mothers, and takes her on a crime spree that only ends when they’re both gunned down. The book is framed as a confession written by the farmer years later, haunted by the rats that infested the dry well he used to dispose of his wife’s body. Having a story framed by a letter is one of those archaic literary framing devices that always strikes me as ridiculous. Who writes a 188 page letter than includes their own transcribed screams as they’re eaten alive by rats?

Inspired by Wisconsin Death Trip, set in Hemingford Home, Nebraska (which had featured in his fiction before), it’s a grim murder ballad sung in stark language. A farmer who believes that his wife wants to sell his land out from under him enlists his son in a murder scheme, but the guilt over what they’ve done festers and grows until his teenage son loses his mind, gets his girlfriend pregnant, busts her out of a home for unwed mothers, and takes her on a crime spree that only ends when they’re both gunned down. The book is framed as a confession written by the farmer years later, haunted by the rats that infested the dry well he used to dispose of his wife’s body. Having a story framed by a letter is one of those archaic literary framing devices that always strikes me as ridiculous. Who writes a 188 page letter than includes their own transcribed screams as they’re eaten alive by rats?

Charles Boone in the aforementioned “Jerusalem’s Lot”, for one. He doesn’t literally transcribe his death screams but his letters and diary include groaners like “I can’t write I can’t write of this yet I I I” and “My mad laughter choked in my throat.” But framing device aside, “1922” was singled out by critics for praise, which it deserves. Like a rough tombstone hacked out of a plank, epitaph inscribed with a pocket knife, this story is raw, elemental, and surprisingly moving. King also uses it to exorcise a ghost that’s haunted him since ‘Salem’s Lot. At the climax of that novel he wanted to use an image of a rat eating someone’s tongue and squirming into their mouth, but his editor forced him to take it out. Here, he finally gets to deploy that image and it’s gross as you thought it would be. You kind of understand why his editor wanted it gone.

Big Driver

Another of King’s stories about a working author on their way to a reading (see “Rest Stop” in Just After Sunset and “Herman Wouk is Still Alive” in Bazaar of Bad Dreams) this time it’s about a cozy mystery writer, Tess Thorne, on her way back from a library appearance. The librarian suggests a shortcut and, like Mrs. Todd in King’s Skeleton Crew story, “Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut”, Tess is a sucker for shaving off a few miles. The detour doesn’t get her home faster, though. Instead she’s ambushed by the titular Big Driver who rapes and, he assumes, kills her, but Tess survives and takes revenge. This is another of King’s Hitchcocks, stories that are short, sharp thrillers (“Gingerbread Girl” and “A Tight Space” from Just After Sunset, “Autopsy Room Four” from Everything’s Eventual). It also points to a slightly discomforting theme in this collection because Tess doesn’t just murder the Big Driver, she also kills the librarian who gave her directions, and Big Driver’s brother. At first she’s tormented by the brother’s death, but then she learns he’s been covering up his murderous sibling’s crimes for years and so she did a good thing. The librarian turns out to be Big Driver’s mother, and she sent Tess right into the ambush on purpose, so she’s fair game, too.

Another of King’s stories about a working author on their way to a reading (see “Rest Stop” in Just After Sunset and “Herman Wouk is Still Alive” in Bazaar of Bad Dreams) this time it’s about a cozy mystery writer, Tess Thorne, on her way back from a library appearance. The librarian suggests a shortcut and, like Mrs. Todd in King’s Skeleton Crew story, “Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut”, Tess is a sucker for shaving off a few miles. The detour doesn’t get her home faster, though. Instead she’s ambushed by the titular Big Driver who rapes and, he assumes, kills her, but Tess survives and takes revenge. This is another of King’s Hitchcocks, stories that are short, sharp thrillers (“Gingerbread Girl” and “A Tight Space” from Just After Sunset, “Autopsy Room Four” from Everything’s Eventual). It also points to a slightly discomforting theme in this collection because Tess doesn’t just murder the Big Driver, she also kills the librarian who gave her directions, and Big Driver’s brother. At first she’s tormented by the brother’s death, but then she learns he’s been covering up his murderous sibling’s crimes for years and so she did a good thing. The librarian turns out to be Big Driver’s mother, and she sent Tess right into the ambush on purpose, so she’s fair game, too.

Coming in at 160 pages (the second-longest story in the collection after “1922”) “Big Driver” is all about control and gender. Tess wishes she was a man at one point because they get to be in charge and control things. She’s interested in cars, something she describes as a “manly interest” and when the librarian (whom she portrays as very butch) asks about her GPS system it’s described as a “man’s question.” If you ever had a doubt that King’s books about cars (Christine, From a Buick 8) weren’t about manhood, this pretty much clears that right up. After all, the person who rapes Tess and who she has to murder to regain control of her life isn’t just a big man. He’s a Big Driver.

Fair Extension

At 62 pages, this is the shortest and least loved story in the book, and it’s easy to see why. The other three stories are all 100% grounded in reality, minus a few hallucinations, whereas this is more in the vein of King’s award-winning, but very blah, short story “The Man in the Black Suit”, also featuring a terribly obvious Satan stand-in, this time named George Elvid (groan). He makes a deal with Dave Streeter, a man about to die of cancer (something that happens to more and more of King’s characters these days): in exchange for 15% of Streeter’s earnings, Elvid will give Streeter fifteen more years of life, and transfer his misfortunes to someone else. Streeter accepts and names Tom Goodhugh, his best friend since grammar school, as the recipient of his woe. They’re best buds, but also Streeter kind of secretly hates him because Goodhugh stole the girl he loved, has a successful business, and a great kid.

At 62 pages, this is the shortest and least loved story in the book, and it’s easy to see why. The other three stories are all 100% grounded in reality, minus a few hallucinations, whereas this is more in the vein of King’s award-winning, but very blah, short story “The Man in the Black Suit”, also featuring a terribly obvious Satan stand-in, this time named George Elvid (groan). He makes a deal with Dave Streeter, a man about to die of cancer (something that happens to more and more of King’s characters these days): in exchange for 15% of Streeter’s earnings, Elvid will give Streeter fifteen more years of life, and transfer his misfortunes to someone else. Streeter accepts and names Tom Goodhugh, his best friend since grammar school, as the recipient of his woe. They’re best buds, but also Streeter kind of secretly hates him because Goodhugh stole the girl he loved, has a successful business, and a great kid.

It’s easy to see why critics didn’t like this story, what with Elvid’s stupid name, his pointy teeth, and the way rain sizzles when it lands on his skin. But those tacky elements conceal a pretty sharp story. Streeter’s problem is that no matter what he gets, he wants MORE, until his hunger makes him a monster. It’s a good description of what’s sometimes called the Wetiko virus, which is a Cree term that is sometimes linked with the Wendigo (remember him? From King’s Pet Sematary?) and means “the consuming of another’s life for one’s own private purpose or profit.” Once infected with Wetiko, “brutality knows no boundaries, greed knows no limits.” Elvid doesn’t literally buy Streeter’s soul, but Streeter’s hunger corrodes the one he has until he’s an empty sack of skin, sitting ringside, popcorn in hand, face painted with sick glee, as he watches his supposed best friend’s life fall apart.

A Good Marriage

Finally we come to probably the best-known story in this book, the shortish (119 pages) “A Good Marriage.” Darcy and Bob have a stable marriage, adult children, and everything is just fine until Darcy wanders into Bob’s workroom and finds a secret door leading to a stash of evidence that points to only one conclusion: her husband is a serial killer. In a way, this is a companion piece to Lisey’s Story, another book about a wife who wanders into her husband’s workspace and discovers his dark secrets. It’s also reminiscent of The Shining, another story about a wife trying to protect her family from her husband’s sick hobby. Darcy tries to hide what she knows from her husband, terrified of what he’ll do to her, but Bob picks up on it right away and instead of murdering her, he proclaims his love for her. What follows is a cat and mouse game as the two of them try to see if they can live with Bob’s secret. More than anything, Darcy wants to protect her family and her children from his crimes, first by ignorance, then by secrecy, and finally through murder.

Finally we come to probably the best-known story in this book, the shortish (119 pages) “A Good Marriage.” Darcy and Bob have a stable marriage, adult children, and everything is just fine until Darcy wanders into Bob’s workroom and finds a secret door leading to a stash of evidence that points to only one conclusion: her husband is a serial killer. In a way, this is a companion piece to Lisey’s Story, another book about a wife who wanders into her husband’s workspace and discovers his dark secrets. It’s also reminiscent of The Shining, another story about a wife trying to protect her family from her husband’s sick hobby. Darcy tries to hide what she knows from her husband, terrified of what he’ll do to her, but Bob picks up on it right away and instead of murdering her, he proclaims his love for her. What follows is a cat and mouse game as the two of them try to see if they can live with Bob’s secret. More than anything, Darcy wants to protect her family and her children from his crimes, first by ignorance, then by secrecy, and finally through murder.

Inspired by media speculation that there was no way Paula Rader, wife of the BTK Killer, wasn’t aware of her husband’s crimes, it’s another late career take on marriage (again: Lisey’s Story). It also embroiled King in a real world kerfuffle when Kerri Rawson, the BTK Killer’s daughter, gave an interview accusing King of exploiting her father’s victims and giving her father, a King fan, an inflated ego. King responded in an open letter to the Wichita Eagle writing, “The story isn’t really about the killer husband at all, but about a brave and determined woman…I grant that there is a morbid interest in such crimes and such criminals…but there’s also a need to understand why they happen. That drive to understand is the basis of art, and that’s what I strove for in ‘A Good Marriage’.” Considering the reason his serial killer murders is because an imaginary playmate tells him to, it doesn’t exactly shed much light on why actual serial killers might kill. What is interesting is his comment that the story is more about the wife than the husband, because this is a book where women win, and men burn in hell.

Full Dark, No Stars was hailed by most reviewers as a disturbing triumph for King and yielded two pretty forgettable movies, “A Good Marriage” and “Big Driver“. And unlike King’s other novella collections, this one has a theme: secrets. Each of the main characters has a secret that twists their lives out of shape. In “1922” the farmer murders his wife and covers it up. That costs him his son and his sanity. In “Big Driver” Tess’s secret (rape and her subsequent triple murder) is the price she pays to restore her life to the way it was, and she’s rewarded for that. In “Fair Extension” Streeter’s hatred of his best friend is his secret, and it ultimately robs him of his soul. Finally, in “A Good Marriage”, Bob’s secret threatens to destroy his family. Order is only restored when his wife gets a secret of her own: she kills her husband and makes it look like an accident, restoring balance and harmony to the world. It’s primitive scale balancing. Big Driver and Bob kill because they’re disturbed and deranged and they are wrong. Tess and Darcy kill for revenge and to prevent more killing, and they’re right. We could also retitle this book The Old Testament.

Full Dark, No Stars was hailed by most reviewers as a disturbing triumph for King and yielded two pretty forgettable movies, “A Good Marriage” and “Big Driver“. And unlike King’s other novella collections, this one has a theme: secrets. Each of the main characters has a secret that twists their lives out of shape. In “1922” the farmer murders his wife and covers it up. That costs him his son and his sanity. In “Big Driver” Tess’s secret (rape and her subsequent triple murder) is the price she pays to restore her life to the way it was, and she’s rewarded for that. In “Fair Extension” Streeter’s hatred of his best friend is his secret, and it ultimately robs him of his soul. Finally, in “A Good Marriage”, Bob’s secret threatens to destroy his family. Order is only restored when his wife gets a secret of her own: she kills her husband and makes it look like an accident, restoring balance and harmony to the world. It’s primitive scale balancing. Big Driver and Bob kill because they’re disturbed and deranged and they are wrong. Tess and Darcy kill for revenge and to prevent more killing, and they’re right. We could also retitle this book The Old Testament.

Full Dark, No Stars also represents a moment when King broke with supernatural horror. All the way back to Cell in 2006, he’d been writing about the supernatural (or aliens), whether it’s zombies, a fantasy world inhabited by a writer, a painter battling zombie children, or a town trapped under a dome. But with three out of his four stories in this book straight up tales of suspense, it marks the place where he (temporarily) starts pushing the supernatural into the background. His next book would be his first full historical novel, 11/22/63, and while it involves time travel and references to It, the book mostly plays it straight. The same with the novel after that, Joyland, which barely brushes against the supernatural, and after that there’s Doctor Sleep, which is most convincing when it’s the least supernatural. Revival doesn’t unleash any otherworldly chills until its final chapters, and his Mr. Mercedes trilogy is a crime series until its final book when, as if he can’t help himself, King returns to full blown supernatural territory. Death and aging play a big part in King’s work, especially as he himself ages. He most likely turned sixty while writing Full Dark, No Stars, and it’s as if he’s seen his own death somewhere up ahead on the horizon and as a reaction finds himself far more fascinated by what’s on this side of the grave.

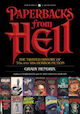

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today. He is the author of Horrorstör, the only novel about a haunted Scandinavian furniture store you’ll ever need, and My Best Friend’s Exorcism, which is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist. His next book is a non-fiction chronicle of the boom in horror paperback publishing in the Seventies and Eighties that followed in the wake of Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and Thomas Tryon’s The Other. It’s called Paperbacks from Hell and will hit shelves in September 19th.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today. He is the author of Horrorstör, the only novel about a haunted Scandinavian furniture store you’ll ever need, and My Best Friend’s Exorcism, which is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist. His next book is a non-fiction chronicle of the boom in horror paperback publishing in the Seventies and Eighties that followed in the wake of Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and Thomas Tryon’s The Other. It’s called Paperbacks from Hell and will hit shelves in September 19th.

Thank you for nother interesting review. I run hot and cold with Stephen King. I only read The Library Policemen from Four Past Midnight and enjoyed it. On the other hand, I finished It because I am stubborn.

And this is why I love the Reread. I bought this book a few years back, read “Big Driver,” and really didn’t like it. I must have donated it to the library afterward because I can’t find it on my shelves anymore. However, Grady’s analysis makes me want to go back and give it a second chance. I don’t even recall what didn’t work for me about the story, except it might have had a few too many of those folksy “King-isms” that work less well for me as the years go on.

Bravo once again, Grady.

While I enjoyed, and was scared, by all of these stories, especially “1922”, I really did notice the violence towards women in this series of stories. Extreme violence against women.

Good, but very, very disturbing, reads.